Border collie reactivity – barking, lunging, snarling, and snapping – is a very common problem with collies. It’s stressful taking them out for walks when they are so noisy and embarrassing, it can be scary and painful attempting to restrain them, and they often restrict our social lives as it’s not easy to have visitors or talk to people when out and about. It’s difficult, upsetting and can be really distressing for our dogs and for us.

However, there is often more to this behaviour than we initially realise, and after practising as a border collie specialist behaviourist for many years now, I have seen first-hand how underlying pain or discomfort is frequently underlying the reactive behaviour, EVEN IF THE DOG IS RUNNING, PLAYING AND JUMPING NORMALLY.

Border collies are natural people pleasers – they want to be in their owners’ good books and hate being wrong. If their owners are experiencing aggressive behaviour with their collies, even extremely intense reactivity, then in most cases it is out of their collie’s control. Usually their arousal is so high while they are reacting, that they can’t even hear their owners, let alone respond to any cues for different behaviour. I have never met a reactive collie who has been simply “stubborn” or “naughty” – there is always an emotional cause of the behaviour and more often than not, they could be in pain.

So how does pain or discomfort cause border collie reactivity?

There are several ways in which pain can affect dog behaviour and cause reactivity:

Physical pain caused by triggers

Dogs that have discomfort may find handling painful, so they may growl and snap to keep people away and prevent painful touch or movement. Or they may have been knocked while playing with other dogs, causing intense pain (Lopes Fagundes et. al., 2018). They may therefore use aggression to keep people or dogs away.

Similarly, the very intense barking, lunging, spinning and attempts to nip traffic that characterises some collies’ fear of vehicles could cause pain and discomfort that the dogs start to associate with vehicles, increasing the anxiety and distress when encountering traffic.Startle or tensing up in relation to a trigger

When dogs see something they are anxious about, it may make them jump, or they may tense up, and this tensing can cause an increase in pain. The dogs then associate this pain with the thing they were worried about. This means that now they are worried about the thing but are also fearful of pain. They bark, lunge and try to bite in an attempt to look big and scary to make the thing go away. (Mills et. al., 2018)

Anxiety in relation to pain

Animals that are in pain may be anxious about avoiding exacerbating pain. They may also become more frustrated if they realise that their options to do this are limited. For instance, a dog may become aggressive when asked to move from a resting position because they anticipate that moving will be painful. (Mills et. al., 2018).

Pain as a stressor

Pain acts as a stressor which can lower the dog’s threshold for reaction. Having pain continually makes us less able to tolerate everyday issues, and we are more likely to snap and struggle to cope. Dogs are just the same. (Walsh, 2025).

When aggression does not make behavioural sense

As behaviourists, we know how to look for the emotions and motivations behind behaviour problems, and if the behaviour doesn’t make behavioural sense, then we start to consider whether pain or discomfort could be a cause.

Owners often think that their reactive dogs are being deliberately stubborn or are ignoring them on purpose, but this is rarely the case. They are just in panic mode and unable to listen.

Studies looking at causes of behaviour problems in the dog population in general in the UK have found that as many as 85% of cases may be caused or exacerbated by pain or discomfort (Mills et. al., 2020). With collies, due to their biddable nature, high intelligence and drive to please their owners, I suspect that this is higher. Anecdotally, I have found that if a reactive collie is also sensitive to handling, and is sound sensitive, then I am definitely looking out for signs of medical issues. Most of the collies I have seen that are reactive to dogs, people or traffic, and are also sound sensitive and fearful of being handled have eventually been diagnosed with some sort of pain or discomfort, so the three issues together are a definite red flag.

Sometimes pain may be the only factor causing the behaviour, and resolving the pain will resolve the behaviour. But more frequently, it may be one of numerous factors that led to the problem behaviour developing in the first place, and is also influential in maintaining the issue over the long term.

Mentioning the possibility of pain or discomfort to owners who come to see me for help with border collie reactivity is difficult, as their dogs often show virtually no physical signs of pain. They run, jump, play fetch, herd sheep, and chase things with no hesitation, and it seems unthinkable that they could be feeling discomfort. I understand this, and I’ve been there in the past – I feel awful when I think back to one of my collies, Blue, who had many signs of pain, that I ignored because he rarely limped or showed any other physical signs.

So to illustrate the point that pain can often be present in reactive border collie, here are a few of the cases that I have seen in the last year in which pain or discomfort was present, contributing to the behaviour problems the dog was displaying.

Theo – 1 year old, entire, border collie

The problem behaviour

Theo’s owner came to me for help with Theo’s extreme reactivity to people, traffic and other dogs. He would lunge and bark at everyone that didn’t live in the home with the immediate family, and often attempt to nip, however many times he had met them. He was the same with unfamiliar people out on walks, and with everyone at the vet practice. He was terrified of traffic and would bark, lunge and snarl at other dogs, and would often redirect aggressively onto his handler.

Unfortunately Theo lived in Basildon on a busy street, opposite a shop and a school so taking him out for walks became so traumatic for Theo and his owners that eventually it was better for everyone, Theo included, that he didn’t have to experience that stress each day. There were no quiet areas within driving distance.

Theo had been to a residential training centre who had worked with him for 3 weeks, but was only slightly improved when he returned home. The training plan developed for him by the centre was good, and as far as we know there was no negative treatment.

Theo had been bought from a breeder on Pets 4 Homes at 12 weeks and hadn’t had any socialisation, meaning that he was terrified of everything. But that alone wasn’t an explanation for his extremely reactive behaviour.

Diagnosis

I immediately suspected that pain or discomfort could be involved in Theo’s behaviour despite there being no obvious physical symptoms, because his anxiety and aggression was so extreme. The vet was unable to examine him, but did not initially suspect pain or discomfort.

Because Theo is so reactive with people, a hands-on examination was not possible. We therefore contacted a Dynamic Dog practitioner, who works with the owner by asking for and examining videos of the dog carrying out different movements and activities. They put a report together to send Theo’s vet, highlighting areas of concern, and exploring potential medical investigations that could be helpful.

Outcome

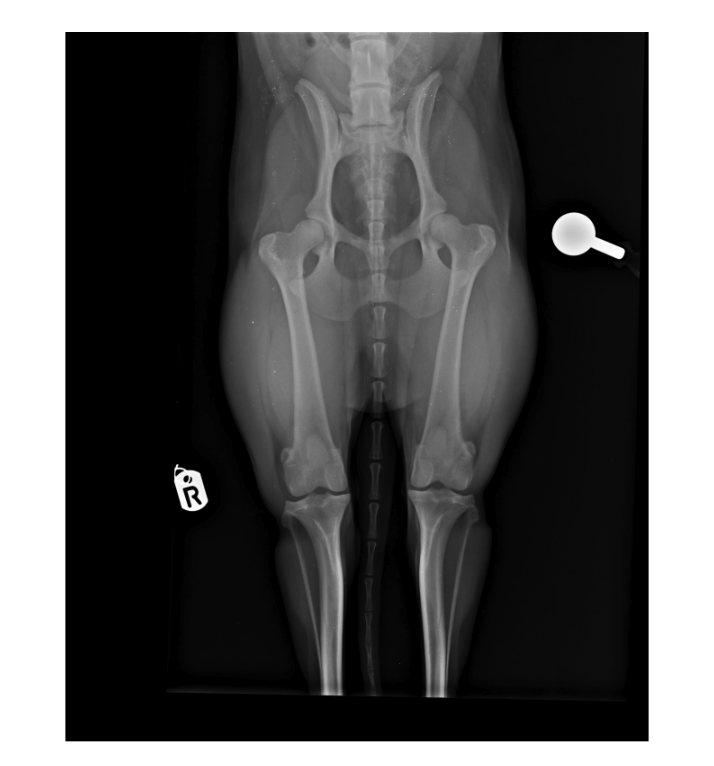

Theo underwent x-rays and was diagnosed with bilateral hip dysplasia, worse on one side, and bilateral (both sides) cruciate disease, where the cranial cruciate ligament ruptures or degenerates causing pain in the hind legs.

He required tibial plateau levelling osteotomy (TPLO), where the angle of the top of the shin bone is changed by cutting and rotating the bone and stabilising it in a new position with a plate and screws. They would start with one side and then may do the other.

This intense pain would have made Theo fearful of interacting with anyone he didn’t know well in case he was knocked or handled in a way that caused pain. Additionally, each time he experienced a trigger that made him anxious, such as people, dogs and traffic, his anxiety would cause him to tense up, causing pain, which he would then associate with the trigger, creating a vicious circle of fear and pain.

Furthermore, when a dog is experiencing pain, they already have a lower threshold for reaction than dogs that are not experiencing any discomfort. We know how much more likely we are to be snappy with others when we have a headache, and are less able to take in what people are saying to us.

All of these factors can add up to the range of problem behaviours that Theo was experiencing.

When I last heard from Theo’s owner she was saving up for the operations required, which were going to be expensive and require weeks of recovery. But at least Theo would be getting the treatment he needed.

Shrike – 8 month old entire border collie cross greyhound/deerhound.

Behaviour problems: Shrike was only 7 months old when I first started working with him. His owners were having issues with seemingly unpredictable aggression towards them in relation to his food, his bed, whenever he was resting on the sofa, and in the car on the back seat where he travelled. He would often show no aggression at all and be very loving, but unpredictably snap at other times.

He was also unpredictable with unfamiliar people, sometimes welcoming strokes and fuss but at other times snapping, causing bruising or bleeding.

Whenever dogs are aggressive towards their owners the alarm bells ring for some sort of pain, and the same when they guard resting spaces. And again, when the behaviour is unpredictable, it can also be a red flag for medical issues. Shrike’s owners were very good with him – they were kind and positive, set boundaries well, and were consistent and predictable – there was no behavioural reason for him to be aggressive towards them. Resource guarding of food can often be caused by gastro-intestinal discomfort, and Shrike suffered from regular diarrhoea and soft stools. So the vet carried out parasite tests, and when these came back clear, we spoke to a dog nutrition specialist. Shrike was quickly settled on a single novel protein diet, and his gut issues seemed to resolve.

However, his aggressive outbursts didn’t improve, and his owners had noted some “bunny hopping” while Shrike was running, and hopping on steps, so he was x-rayed which also came back clear. After this, the vet was unconvinced that further investigations would be helpful, and due to this, the owners had doubts about discomfort being the cause of the issues.

Diagnosis

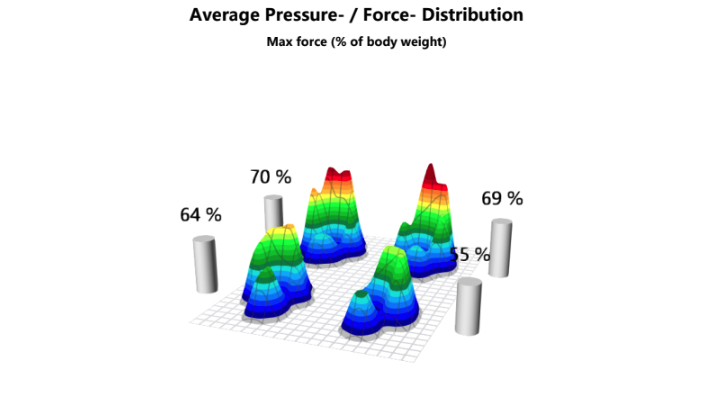

Eventually when Shrike wasn’t making improvements with the behaviour plan alone, we asked for a referral to the Nupsala Musculoskeletal Clinic at Melton Mowbray for gait analysis and physical examination. They noted that despite a normal clinical examination of his right hind limb, and no visual gait abnormality, he was consistently offloading weight from this limb.

He also reacted strongly, once with vocalisation, to direct pressure over the lumbosacral region (lower back where the spine meets the pelvis). The conclusion was that he was experiencing significant pain in this region, which would have been causing his anxiety and aggression when touched in certain contexts, and his dislike of being approached or moved when settled on a couch or in his bed. It was his way of asking people to move away and leave him alone as a way of preventing pain.

Outcome

The first suggested course of treatment was an epidural injection of long acting pain relief (6-12 months) under anaesthetic. The gait analysis would then be repeated after 4 weeks to see if there was any improvement. A course of steroids may also have been required. It may have been necessary to carry out a further MRI or CT scan to find out the exact cause of the pain.

When I last spoke to the owners, they were starting their journey of diagnosis and treatment with Shrike, hoping to resolve his pain issues. They had the skills to continue his training and behaviour plan, and if his pain was able to be controlled, there was every chance that Shrike would start to improve. Unfortunately, it had taken a long time to get to the diagnosis, so his behaviour had been practised for many months, making it more difficult to resolve without lengthy training.

Dave – male neutered 12 month old poodle cross collie

Problem behaviours

Dave was living in a flat in London and was just over a year old when I started working with him. Despite living in a flat with no garden, the owners were amazing at providing all his needs and giving him space and time to run around. The main issue was his jumping and mouthing which had started to become a big problem at around 8 months old, noticeably worse after he went with his owners on holiday to France. Holidays are more traumatic than we realise for dogs, so there may have been anxiety and trauma associated with his behaviour.

The jumping and biting was worse when leaving the house for a walk, when leaving the house without him, on walks and when in pubs or cafes, all times when he was frustrated. He’d been asked to leave daycare and a dog walker had refused to continue walking him after a guarding incident. His female carer had returned from walks many times in tears with bruised and bleeding legs.

Dave didn’t seem able to relax, he never settled and was always on the go, looking for things to chew or steal, or trying to bite and mouth his owners, who thought he was attention seeking.

These sorts of behaviours are very uncommon in collies or poodles of his age, and, with the behaviour really taking hold when he was 8 months old, I immediately started to wonder if pain or discomfort was a cause, as musculoskeletal issues can start to become an issue at this age. Dave showed no physical signs at all of any pain – there were no signs of gut issues, and no lameness or strange gaits. However, when we met up, he had a habit of hanging back behind his owners while walking, and showed some less obvious signs of anxiety and discomfort. Also, his biting and jumping was much worse when the caregivers tried to take him for the last walk of the night when he had been settled, another red flag for pain or discomfort.

Dave had been given the chemical castration implant at 6 months old, due to aggressive behaviour towards occasional other male dogs, which had reduced this behaviour. It could also have started to cause an increase in anxiety at 8 months old, so there were a lot of potential causes of his behaviour and it was a complicated case.

We put together a training and behaviour plan, and Dave’s behaviour improved, but there remained an element of biting and jumping, most notably last thing at night, and his chewing and stealing items improved, but not to the extent that I would expect.

Diagnosis

At about 14 months old, his caregivers made the decision to castrate him. While he was under anaesthetic we also asked the vet to x-ray him to check for any musculoskeletal issues. The x-rays showed mild hip dysplasia in one hip. Even though the issue was mild, pain is very personal and whilst an issue can cause no pain in one person or dog, it can cause a lot of pain in others, and his behaviour fitted with feeling hip pain.

Outcome

The owners were trialling pain medications when I last spoke to them, and were also trialling anxiety medication, with good results, and Dave’s behaviour continues to improve.

Molly, a female entire 1 year old border collie

Problem behaviours

Barking and lunging at traffic, including in the car while travelling, pulling on the lead, excessive barking in the home, at animals on the TV, household appliances (vacuum cleaner, mop, hairdryer, blender, gardening tools such as a shovel), cars driving past, inability to settle in new environments (she would pant and whine if the owners stopped to talk to someone on walks, and was impossible to take into pubs or cafes due to barking/whining).

I’m still working with Molly and she’s a wonderful little dog. We are working on her behaviour and training plan, and she is making a lot of improvement. However, she has suffered from many infections in her short life, from urinary tract infections, anal gland issues, eye infections and most recently tonsilitis. So a lowered immunity is on our list of differential causes of her behaviour problems, and we’re in close contact with Molly’s vet to determine if there is anything ongoing.

However, for the purposes of this article, it was her tonsilitis that highlighted just how much pain can affect behaviour.

Diagnosis

I’d been working with Molly’s owners for a few weeks when, between, our catch ups, Molly’s reactivity to noises, household appliances and triggers on the TV suddenly became much worse. Her caregivers immediately realised, due to our work together, that pain somewhere could be causing this escalation and took her to the vet. When they couldn’t find anything, they decided to sedate Molly to properly check her teeth to make sure there wasn’t a dental cause. While examining her teeth, they happened to notice that her throat was extremely sore and inflamed and that she had severe tonsilitis, which they never would have seen without sedating her.

Outcome

Molly was put on strong antibiotics, and her behaviour gradually returned to its previous levels – but this case is so important to highlight how sudden changes in behaviour can be caused by pain. And it also shows how easy it would have been to miss this – tonsilitis isn’t something vets routinely check for.

Work with Molly continues, and we are still working with Molly’s vet and considering further physical examinations to try to ascertain if there is ongoing pain and discomfort behind her behaviour. We suspect that there is – it’s just finding where.

Esther, female entire 6 year old border collie

Esther isn’t reactive, but I wanted to include her in this article as a nice example of how very small subtle changes in behaviour can be clues to pain or discomfort. Esther is my lovely girl, my main sheep worker, and she has always had an obsession with water, wanting to chase the water coming from the hose incessantly, the more it is moved from side to side the better. These sorts of repetitive behaviours are often associated with pain or discomfort, but as she had no other symptoms or problem behaviours, I didn’t initially follow this up.

However, last summer, for the first time, I noticed her cringing at gun shots while on a walk. The next day she didn’t want to get out of the car in the same location. This set alarm bells ringing, as sound sensitivity is so often linked to pain (Lopes Fagundes et. al., 2018). When she didn’t want to walk the next day, I was even more concerned, and it was then that I realised that her refusal to get off the car seat and into the footwell was quite cramped awkward manoeuvre and that this could be due to pain as well. Esther wouldn’t ignore my requests for no reason.

Diagnosis

So I took her to the vet for a check up. They checked her over really well and didn’t find any cause for concern, but I was still worried. A few months later, I took her in for a dental and asked them to x-ray her while she was under anaesthetic. They felt her again and said she seemed fine, but I asked them to do it anyway.

They called later that day to say that she has mild hip dysplasia both sides, one side slightly worse than the other. I was upset, but at least we knew the cause of the behaviour. She is now on supplements all the time, and medication when she needs it (I judge this by her being less keen to go for a walk). We have rugs throughout the home, which has made a big difference – dogs in pain struggle to walk on slippery floors – it can make their pain worse, so having non-slip mats down really helps. For further information about helping dogs with musculoskeletal issues, the CAM (Canine Arthritis Management) website has some fantastic advice.

Outcome

She is now fine with bird scarers and happy to walk again. I never ask her to make any difficult or awkward movements, and she still has a full and happy life. Luckily her dysplasia isn’t too severe, and she had never shown any signs of pain or limping at all. It was only due to her subtle behaviour changes that I realised what was going on, and just shows how much pain and sound sensitivity are linked.

What next?

By the time pain is diagnosed, I have often been working with the owners for several months, because it can take this long to get to the bottom of things, and get vets and owners on board with the fact that their dog may be experiencing discomfort.

So having worked together for a few months, the owners already have the skills they need to continue working with their dogs. And now that pain has been diagnosed and hopefully treated, they usually make quicker progress than before. In 1983, BV Beaver found that the prognosis for aggression cases was very positive if pain could be treated, with successful treatment outcomes in all the cases in his study (Beaver, 1983).

However sometimes the behaviour problems have been ongoing for several years, and at high intensities, depending on when the owners get in touch. So with these dogs, behaviours may have become very entrenched and are therefore more difficult to resolve. There is often some anxiety also present, because dogs become anxious about anything that causes them pain – this may be sounds, traffic, other dogs, other people etc. This is a very strong learned association and can take a long time to resolve.

However, even with these more difficult cases, I find that once owners understand why their dogs have been behaving in the way that they have, they can better tolerate the behaviour, empathise, and start to protect their dogs rather than blame them. Simply understanding why their dogs had these issues is enough, and they are grateful for the help to resolve this.

References

Beaver, B. V. (1983). Prognosis of aggression when pain is identified as the cause. Veterinary Clinical Case Reviews, 3, 109-112.

Lopes Fagundes, A.L., Hewison, L., McPeake, K.J., Zulch, H. and Mills, D.S. (2018) Noise Sensitivities in Dogs: An Exploration of Signs in Dogs with and without Musculoskeletal Pain Using Qualitative Content Analysis. Frontiers in Veterinary Science, Volume 5 – 2018.

Mills DS, Demontigny-Bédard I, Gruen M, Klinck MP, McPeake KJ, Barcelos AM, Hewison L, Van Haevermaet H, Denenberg S, Hauser H, Koch C, Ballantyne K, Wilson C, Mathkari CV, Pounder J, Garcia E, Darder P, Fatjó J, Levine E. Pain and Problem Behavior in Cats and Dogs. Animals (Basel). 2020 Feb 18;10(2):318. doi: 10.3390/ani10020318. PMID: 32085528; PMCID: PMC7071134.

Walsh, S. (2025). Understanding the link between canine pain and problem behaviours. Veterinary Ireland Journal, Volume 14, Number 2, 75 – 81.