Border collies are consistently over-represented in cases of car chasing, traffic fixation and lunging at moving vehicles (Cooper et al., 2024). Typically, the behaviour is often described as hypervigilance and fixation, followed by barking, lunging, spinning, and—if opportunity allows—chasing. This behaviour presents substantial welfare and safety risks, including injury or death of the dog, risk of the handler tripping or bring pulled into the road, and risk of road traffic accidents. It also increases the risk of relinquishment to shelters as cargivers struggle to cope.

The following video highlights these risks.

Despite its prevalence, car chasing in border collies is frequently explained away as “herding”. While breed-specific motor patterns undoubtedly influence how the behaviour looks, reducing traffic chasing to herding alone oversimplifies a complex, emotionally driven behaviour and risks inappropriate intervention. in this article I’ve taken evidence from ethology, veterinary behavioural medicine, neuroscience, and applied behaviour to outline the primary differentials contributing to car chasing in Border Collies, with particular emphasis on the emotions and motivations behind the behaviour, reinforcement processes, and welfare implications.

It’s also important to remember that other breeds chase traffic, and in their case, it’s not dismissed as “herding”. In these cases, we may think more about other emotional drivers of the behaviour, and that’s what we need to do when working with car chasing border collies. Two recent papers looking at chasing behaviour (Cooper et. al., 2025) and lunging behaviour (Marin et. al., 2026) towards traffic in collies concluded that these behaviours appear not to be a direct expression of herding behaviour, but are more likely to be a result of environmental factors, training, or early socialisation experiences. Cooper et. al., 2025 concluded that the border collie drive to chase vehicles is likely to be more related to impulsivity than herding activity, driven by the increased speed and predictability of traffic as opposed to other triggers.

Breed selection and motion sensitivity (predisposing factor, not diagnosis)

Border collies have been selectively bred to perform a modified predatory motor sequence in which orienting, eye, stalking and chase behaviours are exaggerated, while grab-bite and kill behaviours are suppressed (Coppinger & Coppinger, 2001; Case, 2023). This means collies are bred to react quickly to movement of sheep, able to track and predict trajectories (Völter et al. 2020), and highly motivated to interact with moving stimuli.

Some of the herding trait characterisations favoured by border collie breeders (Arvelius et. al., 2013) include:

- Ability to foresee and counteract the livestock’s movements, to keep the flock together

- How intensely the dog visually focuses on livestock

- Intensity of focus on the herding task

- Cooperation with handler while working

- How wide the dog outruns to get behind the livestock (the balance point) to bring them back to the handler

- How often and where the dog grips (bites) the livestock – occasional nips to stubborn sheep are allowed, but dogs that grip unnecessarily are not.

It’s clear to see that breeding for these characteristics could result in a dog that is impulsive, sensitive to movement, utilises “eye” (visual fixation) to attempt to control, and could potentially nip.

However, these traits alone do not explain car chasing.

Why traffic chasing is unlikely to be a predatory response

Predatory behaviours are thought to be activated by the SEEKING system of mammalian brains (Wright & Panksepp, 2014). So if we are suggesting that car chasing is a form of predatory response, the border collie must perceive the stimulus as biologically relevant. Sheep exhibit biological motion, respond contingently to the dog’s behaviour, have animal odour, and move at speeds the dog can influence. They are clearly prey-like objects.

Vehicles, however, are inanimate, rigid, fast, noisy, non-responsive, do not smell biological and are non-biological in movement.

Research shows that herding breeds are keen to interact with moving animals, and excel at tracking and anticipating moving objects on a screen (Völter et al., 2020), but there is no evidence that dogs, or any animals in general, perceive vehicles as livestock. Wild dogs or large African predators have never been reported to misidentify vehicles as prey or attempt to chase them, despite frequent exposure. Durrheim and Leggat (1999), looking at risks to tourists in South Africa over a ten year period, found that, of all the fatalities and non-fatal attacks, all occurred while the tourists were on foot, apart from one non-fatal attack on a vehicle by an elephant. Elephants are herbivores, so this would not have been a predatory attack.

Marin et. al., (2026) found that there was no difference between working and show line collies in terms of lunging at traffic. Anecdotally I’ve seen that many show line collies show a lack of natural ability to herd sheep, preferring to mix with sheep as though they were other dogs than to attempt to carry out any part of the predatory sequence that comes more naturally to most working line dogs. Yet both are just as likely to herd traffic? Interestingly, the authors found no association between collies that were walked or carried out dog sports every day and lunged at traffic, nor between dogs that took part in search games on a daily or weekly basis and lunging at traffic. So further evidence that traffic reactivity may not be related to “herding” and is not improved by collies having their needs met with other activities.

Given the border collie’s selective breeding for discrimination and precision, it is implausible that they, of all breeds, would be the most likely to misinterpret traffic as prey. Clinically, labelling traffic chasing as “herding” risks normalising a behaviour that completely negatively overwhelms collies and poses a substantial welfare risk, and may encourage “outlet” approaches that are unlikely to help reduce or resolve the behaviour.

Is Traffic Chasing Play?

Traffic chasing in border collies is assumed by some owners and professionals to be enjoyable due to its intensity and the dog’s apparent motivation to approach moving vehicles. If we are ruling out predatory behaviour, this raises the question of whether the behaviour could be caused by activation of the PLAY system.

Most car chasing behaviour begins before collies are one year of age. The function of object play in juveniles is thought to be practise for adult predatory behaviour in predatory species (Hall, 1998), and we have already questioned whether a moving vehicle could elicit a predatory response. Stimuli that reliably activate the PLAY system in dogs are usually other social beings or objects that resemble prey in size, texture, and offer sensory feedback (Bradshaw et. al., 2015), unlike vehicles. Collies can be drawn to play with items that move along the ground, such as brooms and cloths but, again, these share more features with prey than vehicles.

There is no evidence in the behavioural literature that any animals engage in play with large, inanimate objects whose only salient feature is extremely rapid movement. While a lack of evidence means that we cannot rule out play definitively, it seems unlikely.

The behaviour is more consistent with dysregulated arousal, frustration, and anxiety than with sustained activation of the PLAY system.

Differential 1: Fear, startle and threat perception

For many border collies, fear and anxiety are central components of traffic chasing behaviour.

Sudden, rapidly approaching (“looming”) stimuli reliably evoke strong fear responses in all animals (King et al., 2003). Vehicles are:

- Large

- Loud

- Fast

- Often appearing suddenly at close proximity

- Sometimes associated with bright lights and splashing water

These properties make traffic a potent fear trigger, particularly when dogs are walked close to the road on a short lead. Physiologically, fear responses in dogs involve sympathetic nervous system activation and endocrine changes including elevated cortisol and stress hormones (Hydbring-Sandberg et al., 2004), priming fight-or-flight behaviour. In restrained dogs, flight is unavailable. In border collies—historically selected to stand their ground when moving sheep or cattle, rather than retreat—this often results in explosive “fight/repel” behaviours such as barking, lunging, and snapping.

But why do vehicles elicit fear in collies more than most other breeds?

- Many collies start their lives in sheds or kennels on quiet farms in the countryside so are less likely to have encountered fast traffic before.

- Compared to other breeds they have heightened visual and acoustic sensitivity, and are bred to react to sudden environmental change.

- As a breed, they do not have to be able to tolerate noise, and city living, this wouldn’t be an important trait to shepherds.

- Collies are very impulsive and can react before they think.

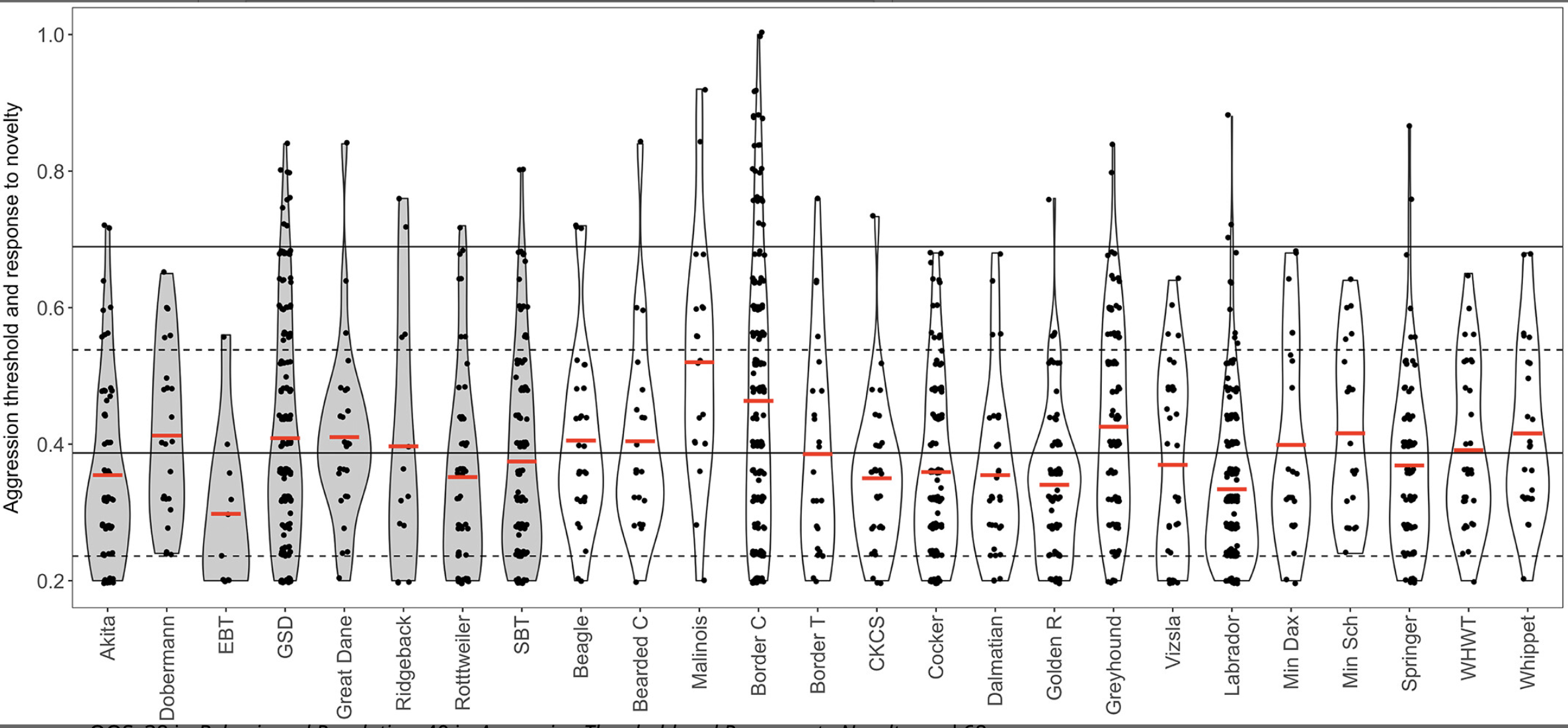

This diagram is taken from Hammond et. al., 2022 and shows a violin plot of “Aggression Threshold and Response to Novelty” scores taken from the the Dog Impulsivity Assessment Scale (DIAS) of the 25 breeds examined in their study. As can be seen in the diagram, border collies scored very highly in this category, with some individuals having the highest scores in the study. The only breed with a higher average score (the red line) in this section of the DIAS was the Belgian Malinois, who are also prone to traffic chasing.

I’ve worked with many car chasing collies, and in most individuals, there is a history of either:

- A one-off event in which they experienced a loud, looming vehicle passing quickly when the collie was still young, potentially causing one-trial learning.

- Puppies are walked next to busy roads, often to “socialise” them to traffic, and are completely overwhelmed, causing ongoing fear.

- Collies may start to car chase during adolescence, often coinciding with a fear period, or development of a musculoskeletal issue

Many collies that car chase initially displayed fearful behaviour towards traffic prior to the development of lunging at vehicles, but this isn’t always noticed by owners, depending on their understanding of dog body language. Inadequate socialisation (including overwhelming dogs by causing fear responses during “socialisation”) during early developmental stages may result in behavioural issues in sensitive and highly responsive breeds such as border collies (Marin et. al., 2026). Research looking at temperament traits of different dog breeds consistently show border collies scoring higher for sensitivity to novelty, impulsivity and negative activation compared to many other breeds (Hammond et al., 2022; Cooper et. al., 2025). Clinically this displays as heightened vigilance, reactivity to sudden environmental changes, rapid increases in arousal, and slower return to baseline arousal.

Many working collies are fearful of sheep during initial exposure, particularly when livestock stand still, stamp or attempt to butt the dog. Dogs that ran away under pressure were useless when working with sheep so would not have been bred from. This has resulted in a population-level tendency to stand their ground under pressure. In modern environments, this predisposition may generalise to traffic contexts, where standing ground replaces avoidance.

Differential 2: Frustration

Frustration is almost always present in traffic chasing cases. Dogs prone to car chasing are necessarily managed on lead near roads, creating a physical barrier that prevents both approach and avoidance.

McPeake et al. (2021) demonstrated a significant correlation between excessive lunging and barrier frustration. When highly motivated behaviours are blocked, negative affect and arousal increase (Howell & Bennett, 2020), posing a welfare concern when experienced chronically (McPeake et al., 2019).

In traffic contexts, the dog may simultaneously want to move towards the stimulus (chase/repel) and away from it (avoid/flight), with both motivations thwarted—creating intense frustration. It’s likely that this frustration behaviour is contributing substantially to the barking and spinning behaviours seen when some collies encounter traffic. It’s this behaviour that makes it impossible to compare the behaviour of collies on lead reacting to vehicles to that of collies herding sheep off-lead.

Differential 3: Predatory motor patterns as emotional regulation (“pseudo-predation”)

Predatory motor patterns are intrinsically rewarding and activate dopamine pathways, which drive feelings of pleasure and reinforces behaviors associated with rewards.. D’Ingeo et al. (2021) argue that predatory behaviours may be recruited during anxiety or frustration because they provide hedonic relief and help the dog to cope in highly arousing contexts.

In border collies, where early predatory phases have been selectively exaggerated, orienting, stalking and chasing may be particularly reinforcing. Under stress, these behaviours can function as emotional self-medication, even when the stimulus is not prey-like.

This helps explain why some dogs appear to “enjoy” traffic chasing over time, despite initial fear, and why the behaviour can escalate even in the absence of external rewards. This could also relate to abnormal repetitive behaviours – see below.

Differential 4: Anticipation and anxiety

Anticipation itself can significantly increase arousal. Anticipation of both rewarding activity and aversive events (anxiety) increase heart rate and stress responses. Studies in working dogs show that anticipation alone significantly alters cortisol, glucose and insulin levels (Angle et al., 2009; Gillette et al., 2006).

For collies that have repeatedly engaged in traffic chasing, anticipation of vehicles may add to an already elevated arousal state, lowering behavioural inhibition and increasing reactivity before the trigger even appears. By the time a vehicle arrives, their arousal is so high that they are completely incapable of regulating themselves, almost like a bottle of pop waiting to go off, with each passing vehicle shaking the bottle then releasing the lid.

Anticipation and/or anxiety that cause a collie to be hypervigilant on walks, always looking out for traffic, can be a welfare concern – they are never able to relax and enjoy their walks by investigating, foraging and engaging in other “normal” dog behaviour. The following video highlights how walks for this collie consisted of anticipation and anxiety, never being able to relax.

Differential 5: Pain and physical discomfort

Pain is an important and often overlooked contributor. Chronic pain is associated with increased impulsivity and reduced emotional regulation (Mills et al., 2020). Dogs with pain are also more likely to show defensive aggression (Mills et al., 2024), which is what we are seeing when collies react to traffic with the “fight” response.

Furthermore, many vehicles are very loud – motorbikes, lorries, buses (with triggering air brakes), rattly trailers and bin lorries are the worst culprits. Collies, as a breed, are very prone to sound sensitivity (Salonen et. al., 2020; Overall et. al., 2016), which has been linked with pain conditions (Lopes Fagundes et al., 2018), and fearful dogs may tense musculature in anticipation of traffic, exacerbating discomfort. Additionally, dogs that car chase often, for their own and their caregivers’ safety, wear head collars, figure of eight collars or harnesses as well as flat collars. Repeated lunging into walking equipment can cause acute pain, further increasing arousal and negative associations with roads, and adding to the “bottle of pop” effect.

Pain should always be considered, particularly in cases with sudden onset, onset at adolescence, escalation, or poor response to behaviour modification alone.

Differential 6: Trigger stacking and cumulative stress

Collies are rarely exposed to one vehicle at a time. It is much more common that they encounter vehicle after vehicle. They are more likely to be able to cope with the first few that they encounter, but repeated exposure to passing vehicles can result in cumulative arousal, often described clinically as “trigger stacking”. Stress hormones persist beyond the triggering event (Overall, 2013), and repeated stressors reduce behavioural inhibition.

Case (2023) describes herding breeds as particularly vulnerable to movement-triggered responses when arousal is high. Once thresholds are lowered, even relatively minor movement can provoke intense chase behaviour, as described in differential 4 above.

Differential 7: Abnormal repetitive or compulsive behaviour

Recent evidence suggests that traffic lunging in border collies may, in some cases, meet criteria for abnormal repetitive behaviour (Marin et. al., 2026). Marin et. al.’s study defines lunging as sudden, forceful forward movement towards moving stimuli and identifies key compulsive behaviour features: escalation over time, generalisation to multiple triggers, persistence despite negative consequences and difficulty disengaging. They also highlighted how it can occur in association with other repetitive behaviours such as light or shadow chasing.

Abnormal repetitive behaviours are stress-related responses often caused by arousal dysregulation, sensitisation and pain, where the behaviour becomes internally reinforcing without resolving emotional distress. Framing the behaviour as herding risks normalising a maladaptive pattern; reframing it as an abnormal repetitive behaviour supports prioritising rehearsal prevention, emotional regulation, and welfare-led intervention. To find out more about abnormal repetitive behaviours, please see this article: A deep dive into repetitive behaviour in border collies.

Differential 8: Fence running leading to traffic chasing

Starinsky et. al., (2017) found that 65% of dogs in gardens have barked at unfamiliar people passing the property. Dogs that are unsupervised, even for short amounts of time, are particularly likely to look for ways of keeping themselves entertained (Raglus et. al., 2015). Certainly in practise, I have seen that collies that are allowed to chase traffic as it passes their garden or home (due to any of the differentials listed above) are more likely to react to traffic when out on walks.

When dogs bark at vehicles and the vehicles carry on passing by, they may conclude that barking and attempting to repel the traffic “worked”. This increases their confidence and leads to the following differential: “the thrill of the chase.”

For collies that enjoy “seeing off” vehicles that pass their garden or home, the first step in helping with car chasing is to prevent this from occurring in the garden or house. Every time they chase a vehicle, they are being reinforced.

Differential 9: “The thrill of the chase” BUT also Frustration

Social facilitation: We’ve examined above whether there can be a positive emotional state that could initiate traffic chasing behaviour, but it doesn’t seem to be either a predatory response or play. However, there is evidence that dogs enjoy running for running’s sake, usually in the company of social companions – dogs or humans. So could moving vehicles trigger a collie’s desire to want to run just for the fun of having something to run alongside? My collies show pure joy in running when we turn round on a walk and they run back past me to start on the return journey. As Coppinger & Coppinger (2001) describe – sled dogs run because other dogs are running – due to social faciliation.

Exercise-induced euphoria: Radosevich et. al., (1989) found that during high intensity exercise, ACTH, ir-beta-endorphin and cortisol increased faster, and the integrated plasma response of these hormones was greater. Similarly, Raichlen et. al., (2012) found that during high intensity exercise, Endocannabinoids (eCB) signalling significantly increased. These hormones and endorphins create feelings of euphoria, reduced anxiety and calmness, as discussed in differential 4 above.

Perceived behavioural efficacy: Once collies have been successfully repelling vehicles and staying safe, either in gardens or on walks, it is thought that their confidence could start to increase. They may perceive that the barking, lunging and spinning is “working”. As the perceived risk decreases, their fear, anxiety and conflict may correspondingly decrease, and it is at this point that if there is any thrill or excitement for collies that car chase, this is when they start to feel it.

So there are various reasons why dogs enjoy running for running’s sake. We can’t know if this is why collies may suddenly want to chase a fast-moving vehicle, but there is currently no evidence to suggest this.

However!

It’s important to remember that because these dogs are not chasing traffic – they are restrained on lead, so any excitement is always going to be tempered by frustration. The collie is never actually able to run and chase. So again we circle back to the fact that traffic reactivity in collies is unlikely to be fuelled by positive emotion. At best it can be excitement about wanting to chase that can never be fulfilled for safety reasons.

In the video below, this dog shows intense frustration behaviours – lunging, spinning, barking and pulling . He may be trying to get to the traffic, but he is not enjoying himself. Interestingly, when walked at a distance from traffic, he would actively try to avoid it. It was only when in close proximity that he attempted to reach it.

Neurochemical modulation and response to anxiolytic medication

An important clinical observation in border collies presenting with traffic chasing is their frequent and often marked positive response to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), particularly fluoxetine, when prescribed and monitored by a veterinary surgeon or veterinary behaviourists. Anecdotally, I have seen significant reductions in the intensity and frequency of lunging, alongside improved emotional regulation and faster recovery following exposure to traffic-related triggers.

SSRIs can lower baseline arousal, reduce anxiety-driven hypervigilance, and improve impulse control (Overall, 2013). Clinically, this reduction in arousal often allows owners and practitioners to “reach” the dog during moments of rising excitement or stress, where previously the dog was over threshold and unable to respond. High emotional arousal is known to impair learning and cognitive processing (LeDoux, 1996; Overall, 2013), and reducing this arousal can make behaviour modification possible for the first time.

The effectiveness of SSRIs in many car-chasing cases further supports the view that fear, anxiety, and/or abnormal repetitive behaviour processes are core differentials, rather than traffic chasing being a simple expression of herding instinct or prey drive. In particular, fluoxetine’s documented efficacy in reducing compulsive and repetitive behaviours in dogs aligns with the presentation seen in border collies whose traffic lunging escalates over time, generalises to multiple triggers, and persists despite negative consequences.

From a neurobiological perspective, SSRIs are understood to modulate serotonergic systems involved in mood regulation, impulsivity, and behavioural inhibition. Their clinical utility in traffic chasing cases is therefore consistent with a model in which arousal dysregulation, emotional conflict, and internally reinforcing motor patterns maintain the behaviour. Medication, where indicated, should always be viewed as an adjunct to careful management and emotion-led behaviour modification, not a standalone solution.

Clinical implications

Car chasing in border collies is rarely caused by a single factor. Instead, it reflects the interaction of breed-typical motion sensitivity with an overwhelming array of emotions that leave a collie extremely distressed and completely unable to regulate their arousal. Fear, frustration, conflict, reinforcement, anticipation, and sometimes pain can all simultaneously co-exist and their sense of threat is amplified. Effective intervention requires:

- Rigorous safety management and rehearsal prevention

- Careful behaviour modification

- Careful pacing to avoid flooding

- Veterinary assessment where indicated

Understanding why the behaviour occurs is essential to reducing risk and improving welfare.

One of my coming articles will be about how to help traffic chasing collies, discussing management and training techniques that work – subscribe to my blog to be alerted to new posts.

References

- Ahmed, A. and Buckley, P. (2013) The Archaeology of Mind: the Neuroevolutionary Origins of Human Emotions, by Jaak Panksepp and Lucy Biven (2012). Journal of Nervous & Mental Disease, 201.

- Angle, Craig T et al. “Hematologic, serum biochemical, and cortisol changes associated with anticipation of exercise and short duration high-intensity exercise in sled dogs.” Veterinary clinical pathology vol. 38,3 (2009): 370-4. doi:10.1111/j.1939-165X.2009.00122.x

- Arons, C. D., & Shoemaker, W. J. (1992). The behavior of collies, huskies, and Shar-Peis toward prey. Applied Animal Behaviour Science.

- Case, L. P. (2023). The Dog: Its Behavior, Nutrition, and Health (3rd ed.). Wiley-Blackwell.

- Cooper, E., Zulch, H. and Mills, D.S. (2025) The role of breed versus personality and other demographic factors in predicting chasing behaviour in dogs. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 282, 106463.

- Coppinger, R. and Coppinger, L. (2001) Dogs-A Startling New Understanding of Canine Origin, Behavior & Evolution. Bibliovault OAI Repository, the University of Chicago Press.

- d’Ingeo, Serenella et al. “Emotions and Dog Bites: Could Predatory Attacks Be Triggered by Emotional States?.” Animals : an open access journal from MDPI vol. 11,10 2907. 8 Oct. 2021, doi:10.3390/ani11102907

- Durrheim, D.N. and Leggat, P.A. (1999) Risk to tourists posed by wild mammals in South Africa. J Travel Med, 6(3), 172-179.

- Gillette, R., Angle, T., Sanders, J. and Degraves, F. (2011) An evaluation of the physiological affects of anticipation, activity arousal and recovery in sprinting Greyhounds. Applied Animal Behaviour Science – APPL ANIM BEHAV SCI, 130, 101-106.

- Hammond A, Rowland T, Mills DS, Pilot M. Comparison of behavioural tendencies between “dangerous dogs” and other domestic dog breeds – Evolutionary context and practical implications. Evol Appl. 2022 Oct 19;15(11):1806-1819. doi: 10.1111/eva.13479. PMID: 36426126; PMCID: PMC9679229.

- Hydbring-Sandberg, E et al. “Physiological reactions to fear provocation in dogs.” The Journal of endocrinology vol. 180,3 (2004): 439-48. doi:10.1677/joe.0.1800439

- King, T., Hemsworth, P.H. and Coleman, G.J. (2003) Fear of novel and startling stimuli in domestic dogs. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 82(1), 45-64.

- Lima, Steven L et al. “Animal reactions to oncoming vehicles: a conceptual review.” Biological reviews of the Cambridge Philosophical Society vol. 90,1 (2015): 60-76. doi:10.1111/brv.12093

- Fagundes, A., Hewison, L., McPeake, K., Zulch, H. and Mills, D. (2018) Noise Sensitivities in Dogs: An Exploration of Signs in Dogs with and without Musculoskeletal Pain Using Qualitative Content Analysis. Frontiers in Veterinary Science, 5, 17.

- McGowan, R. T. S., et al. (2014). Positive affect and task success in dogs. PLOS ONE.

- McPeake, K.J., Collins, L.M., Zulch, H. and Mills, D.S. (2021) Behavioural and Physiological Correlates of the Canine Frustration Questionnaire. Animals, 11(12), 3346.

- McPeake, K., Collins, L., Zulch, H. and Mills, D. (2019) The Canine Frustration Questionnaire—Development of a New Psychometric Tool for Measuring Frustration in Domestic Dogs (Canis familiaris). Frontiers in Veterinary Science, 6.

- Marin, B., Salden, S., Broeckx, B., Van Den Broeck, W. and Haverbeke, A. (2026) Born to lunge? A survey on lunging behaviour and associated factors in Border Collies. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 296, 106894.

- Mills, D.S., Demontigny-Bédard, I., Gruen, M., Klinck, M.P., McPeake, K.J., Barcelos, A.M., Hewison, L., Van Haevermaet, H., Denenberg, S., Hauser, H., Koch, C., Ballantyne, K., Wilson, C., Mathkari, C.V., Pounder, J., Garcia, E., Darder, P., Fatjó, J. and Levine, E. (2020) Pain and Problem Behavior in Cats and Dogs. Animals, 10(2), 318.

- Mills, D.S., Coutts, F.M. and McPeake, K.J. (2024) Behavior Problems Associated with Pain and Paresthesia. Veterinary Clinics of North America: Small Animal Practice, 54(1), 55-69.

- Overall, K. (2014) Behavior Problems of the Dog and Cat, 3rd ed., G. Landsberg, W. Hunthausen, L. Ackerman. Saunders, Elsevier (2013), 472 pp.; $99.95 (paperback), ISBN: 9780702043352. The Veterinary Journal.

- Overall, K. L., Dunham, A. E., & Juarbe-Diaz, S. V. (2016). Phenotypic determination of noise reactivity in 3 breeds of working dogs: A cautionary tale of age, breed, behavioral assessment, and genetics. Journal of Veterinary Behavior, 16, 113–125.

- Radosevich, P.M., Nash, J.A., Lacy, D.B., O’Donovan, C., Williams, P.E. and Abumrad, N.N. (1989) Effects of low- and high-intensity exercise on plasma and cerebrospinal fluid levels of ir-beta-endorphin, ACTH, cortisol, norepinephrine and glucose in the conscious dog. Brain Res, 498(1), 89-98.

- Raichlen, D.A., Foster, A.D., Gerdeman, G.L., Seillier, A. and Giuffrida, A. (2012) Wired to run: exercise-induced endocannabinoid signaling in humans and cursorial mammals with implications for the ‘runner’s high’. Journal of Experimental Biology, 215(8), 1331-1336.

- Salonen, M., Sulkama, S., Mikkola, S. et al. Prevalence, comorbidity, and breed differences in canine anxiety in 13,700 Finnish pet dogs. Sci Rep 10, 2962 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-59837-z

- Völter, C.J., Karl, S. and Huber, L. (2020) Dogs accurately track a moving object on a screen and anticipate its destination. Scientific Reports, 10(1), 19832.

As the owner of 3 border collies (1a lunger) this makes fascinating reading. Thank you.

Thank you for commenting 🙂

My Collie also react the same way to verchiles. When she was little I took her with me on bicycle rides in her basket. Now her behavior make walking a dangerous outing!

My guess is that a few vehicles went by too fast or too loudly and scared her. 🙁

Interesting…

We have a beautiful 3 yr old boy. We live at the base of the Blue Mountains west of Sydney. He has developed to be amazing around home wjth us guests and family at events but walks are a concern. I am a mature fellow and worry that made in 3-5 years we could have issues. Besides medication what other approaches are considered for his walking behaviours.

Lovely to hear from you all the way from Sydney! This article might help – it’s for aggression/reactivity to anything from people, other dogs but applies to traffic as well: https://collieconsultant.co.uk/2023/11/11/border-collie-aggressive-behaviour-what-do-i-do/

My working Collie chased anything that moved while young, I had to teach him what we want to chase and what to leave alone. Chase sheep or herd goats, but leave horses and Lammas, leave quad bikes and cars etc. The sound and movement was the attraction. The relationship between us helped me tell him what was right or wrong, he understood.

This I very interesting- thank you for researching and sharing your findings.

I have a border collie that was re homed to me at 8 months old. She came with a well established car and train chasing behaviour. She once ran 200m to get to a car that appeared on the field where I was walking her. She wanted to bite the tyres but luckily it had stopped by the time she got to it. It’s always the wheels she wants to get to and bite.

I am interested in your next article on training for this issue.

Thanks again,

Cath

Thank you Kath – I’ll try and get the next article out asap.

Our Border Collie did this relentlessly for many years – I eventually took the lead off in places where it was safe and then slowly trained him to walk with me and let my own anxiety fade. He became quite good at this but one day unexpectedly he chased a car and just got nicked on his front paw and nail – gave him a and me a big scare. But he was OK – he returned to a quiet pattern after that – but of course I stayed vigilant when a car approached – I put it down to the same sensitivity to noise such as vacuum cleaners, lawn mowers and the posties motorbike. Cheers John and Castiel

Yes there are a lot of factors about traffic that could cause collies anxiety from the sound (many are worse with loud vehicles), to the sudden appearance, to the “looming” effect that all animals are typcially anxious about, the smell, the movement – it’s all so overwhelming for such a sensitive breed.

Excellent article. looking forward to more, especially on therapy for a car-chasing collie.

Thank you!

THANK YOU!!!!! .FInally, someone who has a real understanding of what a car panicked dog is. We have sibling BCs – the male started reacting at 6 months, we can’t walk in our neighbourhood at all. Even empty country lanes put him on full alert. His sister couldn’t care less about traffic of any kind..

Unfortunately this is the reality for so many collie owners – having to go somewhere quiet for walks. Even if they only live 100 yards from a quiet track, they still need to drive there.

Toller Artikel. Mein BC verhielt sich auch seit seiner Pubertät genau so. Bis ich herausfand, dass er aus Angst nach vorn ging. Also habe ich ihm mit Kommando “kehrt” beigebracht, sofort den größtmöglichen Abstand zur Straße zu suchen (90°- Winkel) und sich dort abzulegen. Das entspricht seinem Wunsch nach Abstand und Versteckmöglichkeit. Ich selbst stelle mich schützend zwischen ihn und den Verkehr. Seither brauche ich kein Kommando mehr. Er reagiert situativ nach Tagesform- manchmal kann er sogar unberührt weiterlaufen, an schlechten Tagen hört er das Auto und legt sich ab. Mit Blickkontakt fragt er mich danach, ob die Gefahr vorüber ist und wir weiter gehen können. Er weiß jetzt, dass ich ihn verstehe und wie er mit der Situation umgeht. Aber es wird nie eine entspannte Situation.

It’s lovely to hear from you, and well done for helping your collie in this way. It’s an interesting training technique and one I will bear in mind in future articles – thank you for sharing it with me! 🙂

Thank you very interesting