What are abnormal repetitive behaviours?

Abnormal repetitive behaviours, also known as compulsive or stereotypical behaviours, are defined as repetitive, constant, and appear to serve no obvious purpose. In border collies they can often be repeated over long periods of time, and some dogs can spend up to 90% of their waking hours carrying out these behaviours. This can negatively affect the dog’s relationships with its owners and other dogs, and prevent the dog from engaging in normal, healthy dog behaviours. When dogs spend this much time engaging in repetitive behaviours, it is seen as a welfare risk.

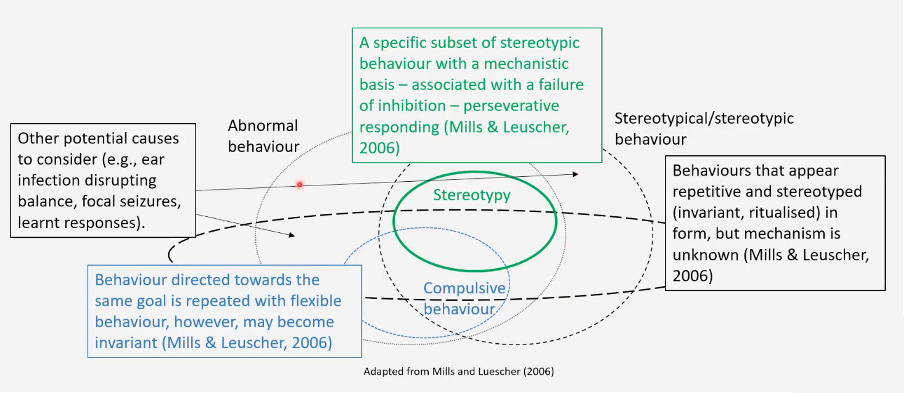

Abnormal repetitive behaviour is an umbrella term for different subsets of repetitive behaviour, and, due to the wide range of different terminology used, Mills and Luescher (2006) categorised such behaviours as follows:

Stereotypical behaviour: repetitive behaviours that are invariant or ritualised but the mechanism causing these behaviours is unknown.

Stereotypies: performing the exact same invariant behaviour or rituals over and over again, with the animal unable to be distracted. There is no obvious function for the behaviour. These are thought to be coping strategies that help the animal to endure pain or discomfort, or a difficult environment. It is relatively rare in companion animals.

Examples include pacing the exact same path, as seen in zoo animals, and fly snapping, where the dog appears to snap at invisible flies.

Compulsive behaviours: directed towards the same goal (eg. fixating on shadows, splashing in water or tail chasing) and the behaviour is varied – dogs may move around to watch shadows, lick different parts of their body, or do fast or slow tail spins depending on their level of arousal.

What repetitive behaviours do we see in collies?

Collies, unfortunately, are one of the breeds that tend to be more prone to repetitive behaviours, indicating there is a genetic element to this behaviour. And there is evidence that repetitive behaviour can run in families, so it’s common to find that many generations may be affected. And, interestingly, the repetitive behaviours practised can be different within family groups, revealing that animals can be prone to repetitive behaviours in general rather than susceptible to one type of behaviour (Overall & Dunham, 2002).

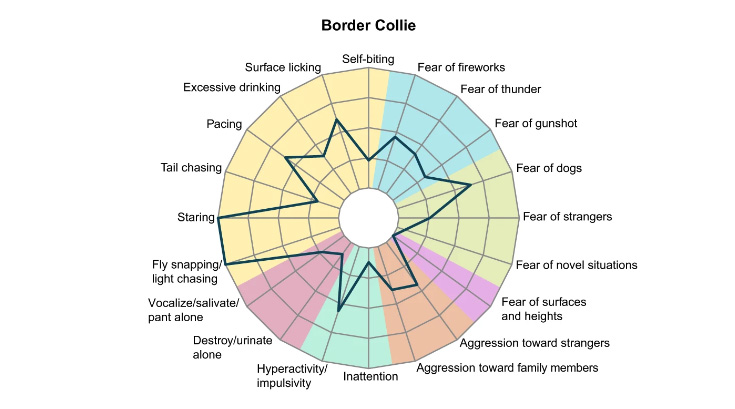

The following chart is taken from a 2020 research paper (Salonen et. al., 2020) which looked at the different types of anxiety found in different breeds of dog. Repetitive behaviours in collies are often due to anxiety, so were included in the research. The chart shows clearly that fly snapping, shadow/light chasing and “staring” (meaning fixating on things such as shadows without chasing) are the most common border collie repetitive behaviours.

What can cause Abnormal Repetitive Behaviours?

Health issues

Issues such as gastrointestinal issues, musculoskeletal issues, hormonal conditions, hypothyroidism, epilepsy, disease, toxicity, can cause or exacerbate abnormal repetitive behaviours. Just saying “get your collie checked out by a vet” isn’t always helpful. Without a specific idea about what to look for, vets are limited in what they can check, so to give your vet more information, record a gait video, and start to keep a diary noting any potential health issues, such as:

- Limping

- Refusing to jump onto a surface (eg. cars or sofas) that they would usually be ok with

- “Bunny hopping” (when the dog moves both back legs together when trotting or walking like a bunny would)

- Loose stools or diarrhoea

- Vomiting

- Growling or snapping if knocked or asked to move when sleeping

- Growling or snapping when being groomed in certain areas

- Also note any sound sensitivity, as this can often be linked to pain (Lopes Fagundes et. al., 2018)

Oral compulsive behaviours (repetitive licking, chewing, barking or fly snapping), particularly, can be linked to gastrointestinal (GI) issues. Bécuwe-Bonnet et. al. (2012) showed how the diagnosis and treatment of GI issues resolved repetitive licking of surfaces behaviour in 9 out of 17 dogs.

Injuries

Any painful injury can initiate repetitive behaviours in collies, even if the pain is brief and the dog is fully recovered from the injury. Two shadow chasers I have seen both started fixating and watching shadows after injuries – one ran into a goal post and hurt his shoulder. The other had a very painful injured nail bed.

Genetic issues

Because dogs suffer from repetitive behaviours in the same way that humans can, there has been a lot of investment in research to investigate if genetic causes in dogs can contribute to, or cause, repetitive behaviour. Several common genetic elements in the brain structure and neurochemistry of animals and humans that perform repetitive behaviours have been found, and research is still ongoing.

The main difference between human obsessive compulsive disorders and compulsive behaviours in dogs is that we can’t know for certain if dogs have the obsessive thoughts that initiate the behaviours in the same way as humans do. For this reason, the word “Obsessive” is not used in recent articles about compulsive disorders in dogs (Luescher, 2003).

One theory about why certain humans and dogs can be more prone to repetitive behaviours is that the internal brain mechanism that should tell the individual to stop performing the behaviour is faulty. Mills & Luescher (2006) go into this be in more detail. And more can be read about this in Noh et. al., 2017.

Whitehouse et al, 2007, found that a strain of mice that perform high rates of repetitive behaviours struggled more with reversal learning in a task than control mice. They were first taught that, out of two identical pellet dispensers in each corner of their cage, only one of the dispensers would dispense pellets. The task was then reversed (the previously redundant dispenser then dispensed the pellets and the previously active dispenser was redundant). The mice that had high rates of repetitive behaviours attempted to access pellets from the inactivated dispenser long after the other mice had learned to use the new dispenser. Interestingly, if these mice were given enrichment, they performed better at reversal learning, but still not as well as the control mice.

It is therefore thought that animals prone to compulsive behaviours struggle to learn that by practising the repetitive behaviour, they are no longer achieving their goal (whatever that goal may have been when the behaviour was initiated). (Langen et. al., 2011). E.g. when chasing shadows they are never able to “catch” the shadow.

Epigenetic issues

Epigenetic changes are modifications to an animal’s DNA that regulate whether genes are turned on and off. This can occur if a bitch is subject to any type of stress while pregnant. Her anxiety can trigger cgenetic changes in her offspring which make them more likely to react to perceived danger throughout their lives than puppies born to bitches who experienced less stressful pregnancies. This is an adaptive strategy and it is nature’s way of ensuring that animals can operate in the environment that they are born into. If that environment is dangerous, then an animal that reacts to that danger quickly and can keep itself alive is better prepared than an animal that feels little fear and wanders into danger at every opportunity (Tatemoto et. al., 2022) .

Early trauma

The first eight weeks of life for puppies while with the breeder are very important. If puppies themselves experience ill treatment or observe their mother being treated badly, their likelihood of having an anxious, fearful temperament is increased (Corridan et.al., 2024). Very young puppies are more vulnerable than adults due to their behavioural immaturity, temperamental pliability, and lack of resilience. These early experiences determine their adult behaviour and temperament, and McMillan et. al. (2015) found that dogs that have been subject to abuse were more likely that a control group to exhibit repetitive behaviours.

Early weaning and maternal deprivation

There is some evidence that dogs that are weaned too early (before 8 weeks old) can be more prone to repetitive behaviours. Tilra et. al. (2012) found that tail chasing German shepherd dogs, bull terriers and Staffordshire bull terriers had experienced lower quality care and were separated earlier from their mothers than the control dogs.

Anxiety/Stress

Collies have been bred for hundreds of generations to excel at working on a quiet hillside with only the shepherd and sheep present. After working they would come home and either rest in the yard or be put back in their kennel (usually individual kennels). They usually weren’t brought into the house to live with the family and they didn’t meet many other people or unfamiliar dogs. Collies bred for this lifestyle didn’t need to be social with lots of people or other dogs and they didn’t need to be able to cope with the ups and downs of family life.

So our collies today, inherently anxious in loud, busy, very social environments, often struggle to cope in homes in which other breeds would thrive. This is particularly true when collies are taken to live in busy towns or cities. Many can’t cope and often need medication to enable them to live these sorts of lives.

Family life inevitably involve tension at times – shouting, arguments, tensions between individuals, angry, upset teenagers, the issues that sometimes accompany neurodivergence or poor mental health, loud crying or over-excited children and tired parents, the list goes on. Our collies can be negatively affected by these things, and it is quite common for collies to be able to relax during the day, but start to practise repetitive behaviours when everyone comes home in the evening. There may be many reasons for this, but the noise, tensions and other added stress that this can bring is certainly one of them.

One collie I was working with developed shadow chasing while his owners were going through a very messy divorce. Once one of the owners left the home, his shadow chasing improved drastically and eventually resolved.

Sometimes things external to the home can be stressful, such as the noise of living in a city, gardens surrounded by neighbouring dogs, particularly if those dogs are very vocal, other dogs they may meet on walks, traffic, unfamiliar people coming into the home or on walks. Basically, anything that can cause a dog anxiety or stress can contribute to abnormal repetitive behaviours.

Social isolation

Dogs are social animals and if they are left alone for too long they become anxious and bored, even more so if they are left crated or in restricted space. If this happens regularly, stereotypies can develop. Stereotypies are a fixed, invariant form of repetitive behaviour and are thought to be a coping strategy, and to give the body and mind something to do. Once established, stereotypies can be very difficult to resolve, and may continue to be practised long after the dog has been removed from the isolated situation.

One spaniel I worked with had been shut in a room with several other dogs for months before she was rescued at 7 months old. She would repetitively spin at times of high arousal, and in this case it had been a coping strategy to help her manage her life in the small enclosed space. Her behaviour very slowly improved once in her new home, but would still occur when she met unfamiliar dogs or in open outside environments.

Psychological stress or Trauma

A wide range of environments can cause stress to individual dogs, especially collies, which, as a breed, are more likely than other breeds to be very sensitive and easily scared. Collies can be left traumatised by incidents which, to us, may not seem particularly traumatic. Trauma is very personal, and things that cause trauma to one dog may not remotely bother another.

As well as the more obvious causes of trauma that we see in rescue dogs, or in dogs that have been treated badly, trauma can also be caused by the following:

- Issues within the owner’s family (mental health challenges, substance abuse, domestic violence)

- Caregiver absence

- Aggression between dogs in the household

- Early separation from mother and siblings

- Routine procedures such as vaccination, microchipping or neutering

(Corridan et. al. 2024)

d’Angelo et. al. (2022) looked at a case study of tail chasing in which trauma and social isolation are thought to have initiated and maintained tail chasing behaviour in a German shepherd dog.

Frustration

Frustration occurs when an animal’s goals are thwarted. Boredom (see below) is a form of frustration. Being frustrated is an unpleasant experience, taking us away from our natural balance of homeostasis, causing stress.

Frustration has a huge part to play in how repetitive behaviours develop and are maintained. Animals that practise compulsive behaviours are trying to achieve something, even if their goal seems out of context. So, for example, when fixating on shadows, collies are anticipating shadow movement. When it doesn’t move or they can’t catch it, they start to become frustrated and that is when they start to circle and pounce on the shadow. Unless it’s their own shadow, then the shadow still doesn’t move and so they become more frustrated, and try harder to get it to move, and so on. The same can happen with tail chasing – the dog is trying to catch their tail but they can’t, so they get frustrated and try harder and so on… The behaviour starts to go on for longer and longer, and the dog becomes more and more frustrated as their arousal increases. These high levels of frustration can cause dogs to switch off from everything around them in an effort to focus all their attention on achieving their goal, so they are unable to be distracted.

Social conflict

Ongoing conflict between the dog and other individuals (human, canine or even feline) in the home can cause anxiety, which can cause repetitive behaviours. If owners continually chastise a puppy for doing things they don’t like, instead of setting up the environment (using puppy pens and stairs gates, keeping chewable items out of reach etc) so that he can succeed, then a dog can feel very conflicted. He loves his owners and depends on them for everything, but they are often angry and may shout, causing fear and stress. The same can happen if there is another dog, cat or other animal in the home that is controlling or aggressive.

If owners don’t spend time training or playing with their collies, and if their interactions are unpredictable and inconsistent, then dogs can become anxious. Setting up the environment so that the dog can succeed and be praised can help to ease social conflict, and so can building their confidence using play, scent training, proprioception, as well as dog sports such as hoopers, agility, tracking and so on. If you have two animals that don’t get on, seek help from a behaviourist. Sometimes rehoming one of them is a kinder option for both animals in difficult circumstances.

I have seen collies start to perform repetitive behaviours when one person comes home for the day. I have seen repetitive behaviour in a collie worsen when teenagers were going through an exam period, and I have also seen a collie only perform repetitive behaviours when a member of the household was very vocal and aggressive while gaming (playing video games).

Displacement behaviour

Displacement behaviours are often misdiagnosed as repetitive behaviours. Displacement behaviours are normal behaviours that are performed at an inappropriate time, appearing out of context. They tend to occur when an animal is conflicted about something. Examples include jumping up visitors – some dogs that are a little worried by visitors may jump up because they are unsure what else to do, or scratching their ear when they want something from a more senior dog who is displaying warning signals, such as in the video below.

In this video Kite is trying to communicate “Look, I’m no threat – I’m scratching my ear”!

Sometimes dogs can chase their tail or start to look at shadows in these situations and if you start to see this happening, it’s important to prevent your dog from practising the behaviour. Managing the dog’s environment so that he/she isn’t exposed to conflicting situations can help to reduce the dog’s anxiety. This helps to reduce the dog’s need to practise the displacement behaviour and prevents it from generalising into other contexts.

Boredom, lack of enrichment or lack of exercise

Research has shown that a lack of enrichment, exercise or boredom rarely cause repetitive behaviours. Overall and Dunham, (2002) found that “(Repetitive behaviour) in dogs does not appear to be associated with lack of training, lack of household stimulation or social confinement”.

Similarly, a study looking at tail chasing in bull terriers and German shepherd dogs found that the following environmental factors were not linked to tail chasing:

- Amount of exercise

- Amount of activities

- Time spent alone

(Tiira et. al., 2012)

And Hall et. al. (2015) found that “stereotypic behaviour may NOT simply be a response to deprivation” (“deprivation” was defined as only occurring when crated or when there is a lack of stimulation).

All of these papers show that, just as in people, boredom alone is rarely a cause of repetitive behaviour (unless it is due to excessive negligence). Unfortunately too many people are told that their dog is performing the behaviour because their dog is bored, and they are not exercising or playing with the dog enough, or not providing enough toys or enrichment. This can stop people coming to behaviourists and other professionals for help, due to feelings of guilt that they are not providing enough enrichment, exercise or stimulation for their dogs, but this is rarely the case.

Attention seeking

Dog, especially collies, learn very quickly, and owner reactions can influence the development of the behaviour. Videos of dogs performing repetitive behaviours are a common sight on the internet, often with tags such as “funny” or stupid dog”, and people can be heard laughing in the background. This is often the first response before owners realise, as the dog starts to practise the behaviour more and more, that it is no longer funny. But it is thought that dogs might find the attention encouraging, prompting them to continue.

Even telling dogs to “stop” is giving them attention, as is giving them a toy or calling them over with treats to distract them from the activity. And, unfortunately, even if you suspect that your dog is carrying out the behaviour due to trying to get attention, ignoring them rarely works. This is because it’s very difficult to do this consistently – and even occasional instances when we do respond to the dog can be enough to maintain the behaviour.

Hall et. al, (2015) looked into whether different types of human behaviour made dogs practise repetitive behaviour more or less. They found that attention from humans (either laughter/praise or asking the dog to stop) made little difference to shadow chasing. But that human attention for circling and repetitive licking behaviour was likely to increase these behaviours. The sample numbers were very small, but an interesting study none the less.

Diet

There is some evidence, particularly with the oral types of repetitive behaviour – licking, barking or fly snapping – that diet may be involved. One of the prevalent ongoing areas of research at present, looking at the gut microbiome, may yield really interesting information about this over the next few years.

One paper looked at how diet change alone resolved fly catching syndrome in a French bulldog within 3 months (Galli et. al., 2024).

Allergies or skin conditions (Pruritic dermatoses)

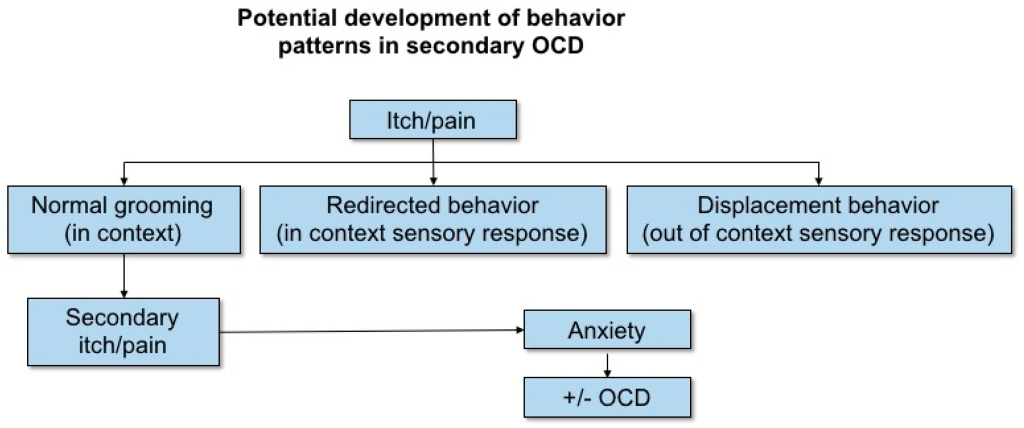

Harvey et, al, (2019) found that any causes of itchy skin, such as allergies or skin conditions was associated with stress which caused problem behaviours such as mounting, chewing, hyperactivity, copraphagia (eating faeces), begging, stealing food, attention seeking, excitability, excessive grooming and reduced trainability. The authors suggested that conditions that cause itchy skin could, due to stress, lead to abnormal repetitive behaviours, such as overgrooming/self mutilation, spinning, tail chasing, shadow chasing and fly snapping.

Although the authors weren’t looking at other symptoms of allergies such as painful ears or eyes, issues with anal glands and gastro intestinal issues, it makes sense that any irritation or pain from allergies could also be associated with repetitive behaviours.

Diagram taken from Harvey et. al. (2019) who borrowed it from Overall (2013).

Types of abnormal repetitive behaviours in collies

There are several classes of repetitive behaviours, and it is thought that different classes can potentially be caused by slightly different factors.

- Locomotory behaviours: circling, tail chasing, pacing, chasing lights/shadows, or watching/chasing reflections, splashes or ripples in water. Light/shadow, water, sand or other observing movement-based behaviours are more common in collies and spaniels, possibly because these breeds tend to be drawn to movement. I have seen several collies that spin or pace, often in relation to pain or discomfort. Tail chasing is more common in GSD’s and bull terriers.

- Oral behaviours: leg or foot chewing, self-licking or licking/chewing of objects, air or nose licking (often looks like gulping), flank sucking, pica (eating inedible objects such as stones). Research tells us that oral repetitive behaviours can be caused or exacerbated by gastrointestinal issues (Bécuwe-Bonnet et. al., 2012), and in several studies, a change of diet has resolved the behaviour (Galli et. al., 2024).

- Vocalisation behaviours: rhythmic barking, or whining. There is not so much research on these types of behaviours, and as a form of repetitive behaviour, they often accompany another compulsive issue, such as shadow chasing, or spinning. Anecdotally I have found these types of behaviours are often related to pain or discomfort.

- Hallucinatory behaviours: fixating on shadows/lights, or just fixating on floors in case shadows/lights appear, fly snapping (snapping at what appears to be invisible flies). Fly snapping is also thought to be related to gastrointestinal issues, similar to oral behaviours. And fixating on shadows/lights etc is included in this group, but is thought to have similar causes to the behaviours in the locomotory group.

(Diagnosis and management of compulsive disorders in dogs and cats. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract. 2003 Mar;33(2):253-67, vi. doi: 10.1016/s0195-5616(02)00100-6. PMID: 12701511.)

Shadow chasing

Shadow chasing is a generalised term that includes fixating on, or chasing, shadows, lights or reflections and is the most common repetitive behaviour seen in border collies.

Shadow chasing can often start in young dogs of 4-6 months old, possibly because they have noticed shadows or lights and started to watch them. Owners sometimes find this amusing to start with, and may encourage it, but it can very quickly get out of hand. Laser pointers are a typical way that this sort of behaviour can start, as are reflections from watches or cutlery. However, a study looking at factors that reward different repetitive behaviours found that the trigger (shadow, light or reflection) moving about was the main reinforcer (Hall et. al., 2015).

Daphne, in the following video, was about 5 months old when she started chasing shadows, and after her owners realised that within a few weeks she was chasing shadows 90% of the day, they got in touch for help. Because her owners got in touch straight away, and by carefully following the behaviour modification plan, she had almost stopped chasing within 6 month. Read more about Daphne’s story.

A very common time of year for shadow chasing to start is in the Autumn, particularly when the clocks go back (in the UK) and dogs suddenly start to be walked in the evenings under street lamps. This causes shadows to move and change shape as the dog and owner walk. Similarly, light chasing can often start at Christmas when there are multiple flashing, moving lights.

Any shadow chasing that starts suddenly in older dogs could be linked to an injury or chronic pain, so always have your dog checked out by a vet, as described above. The dog in the video below started shadow chasing following an incident in which he ran into a goal post and hurt his shoulder. This happened to occur at the same time as the clocks change in the Autumn, so that he was seeing more shadows caused by street lights on walks, creating ideal conditions for the development of shadow chasing.

Water and other fixations

I have seen two similar behaviours to shadow chasing relating to water and sand in collies. Collies are so often drawn to movement, and the movement of water coming out of a hose can be very stimulating, with collies often wanted to “catch” the water. They can also fixate on water (waiting either for reflections to move or for ripples) or on sand (watching it blow in the wind, or be moved by owners’ feet as they walk).

In the videos below, Bo is fixating on the water coming out of the taps, and trying to bite it. Because water is something physical that can be “caught” then this often isn’t classed as a repetitive behaviour, and luckily avoiding water is much easier than avoiding shadows. Bo was eventually diagnosed with a painful tear in a shoulder muscle and is still undergoing treatment. You can read more about Bo in this article.

Kato, in the video below, likes to hold a piece of seaweed in his mouth while watching the sand move. It is very likely that he was suffering from hip pain or discomfort, and his owner is still considering asking for further vet investigations.

Treatment for shadow/water/sand fixation or chasing

Treatment for shadow/water/sand fixation or chasing will depend on what is contributing to the behaviour, but behaviour plans usually include:

- Limiting the dog’s access to triggers (the shadows, lights, reflections, water or sand). This can be achieved by keeping dogs away from areas in which they practise the behaviour, or by managing the environment – for example, keeping keeping the curtains drawn and not using lights in the short to medium term.

- Keeping a diary to determine when the dog is most likely to perform the behaviour (e.g. sun coming through kitchen window in the morning/evening, reflection when the back door is opened or while family meals are being prepared causing movement of the owners and lots of moving shadows), as well as recording any times when the dog does NOT practise the behavour.

- Reinforcing any times when the dog is awake and is not shadow chasing by praising them and giving them attention.

Preparing activities to give the dog to do so that, even if they see shadows, they can be engaged in something else that is more enjoyable. This MUST pre-empt the shadow chasing so that the dog isn’t being rewarded. So at times when you know the dog will start to chase or fixate on the trigger, present the first activity, then take the dog into the garden to the toilet (unless they chase shadows in the garden) which acts as a reset, then start the next activity. The aim is to get the dog out of the habit of chasing shadows and teach a new incompatible behaviour.

Tail chasing and spinning

This is less common in collies, but I have still seen several cases. Holding and chasing the tail, fixating on the tail, circling in tight or wider circles, or nibbling at the tail all come under the umbrella term “tail chasing”. It can be related to pain in the hips, back or tail, and 90% of the dogs I have seen that chase tails, circle or pull hair out of the tail have had hip or spinal problems.

Gloria, a beautiful 2 year old border collie presented to me with circling behaviour, which would continue throughout most of the day. She would occasionally limp or scuff her paws while walking and over time this became more frequent. She was eventually diagnosed with hip dysplasia and arthritis in both hips.

Similarly, Meg, only a year old, would bite and chase her tail whenever she heard a noise of which she was afraid, such as aircraft, road works, and any other loud bangs, crashes or machinery noises. She was also very scared of traffic. She was also diagnosed with hip dysplasia, and improved dramatically once on pain relief.

You can read more about Meg and Gloria in this article.

As with all repetitive behaviours, it could be initiated by any of the above causes, but, like shadow chasing, is a behaviour that owners often find amusing to start with, meaning that it may have been inadvertently reinforced.

A 2015 study (Hall et. al.) based on owner reports found that tail chasing is most likely to occur when the dog is stressed, and I have seen that it is often performed at times of high arousal, such as during greetings or when getting ready to go out for a walk.

Fly snapping

The repetitive behaviour termed “fly snapping” usually does not involve actual flies. The dogs are just snapping at the air, just as if they were looking at, and trying to catch, flies or bits of dust in the air. It can occasionnally start with the collie snapping at real flies or dust, but then progress to snapping at nothing.

This can sometimes occur in collies, and comes under the “oral” or “hallucinatory” categories of abnormal repetitive behaviours and is often linked to gastrointestinal issues. It is thought that extending the neck up as if to catch flies lengthens out the gastrointestinal tract, perhaps creating relief from pain or discomfort. In one study, the authors describe how changing the diet of a French bulldog stopped the dog from fly snapping within 3 months (Galli et. al., 2024).

In the videos below, Mowgli would get very anxious about flies in the house, and would watch them through the window and try to get to them. In the garden he would sit and watch the flies and jump to snap at them. This would be so frequent that it was becoming distressing for the owners, and was stopping Mowgli from being able to settle and relax. This often isn’t classed as an abnormal repetitive behaviour because there is something there that he can see and could catch. However, the treatment is the same.

Licking of carpets/fabrics/floors

This is another type of oral repetitive behaviour and can also be linked to gastrointestinal (GI) pain or discomfort. Bécuwe-Bonnet et. al. (2012) found that of 17 dogs that repetitively licked surfaces, GI abnormalities were found in 14. After treatment, 10 out of 17 dogs improved significantly (59%). If your dog repetitively licks surfaces in your home, and you have noticed loose or soft stools occasionally in your dog, speak to your vet about a full GI checkup, thinking about ruling out such things as irritable bowel syndrome, the presence of a foreign body, pancreatitis, giardiasis, and any allergies. Your vet will know more about this.

Reuben, in the video below, is a collie cross spaniel who would perform this licking behaviour on all hard floors in the home at times of very high arousal. It seemed to morph a little into pouncing and fixating, similar to shadow chasing.

Digging on hard surfaces in the home

Dogs will often dig in cupboards, fireplaces or on hard floors, for no obvious reason, and, as with most repetitive behaviours, it is very important to rule out pain. This can often be related to musculoskeletal issues.

When the behaviour occurs is relevant. If it only happens when owners are present, then the dog may be attention seeking, or the dog may be stressed for a different reason when the owners are present. However, if the dog only does it when he is left alone, then the dog could be digging in an attempt to escape, caused by separation related problems. So, as usual the context is very important.

In the video below, Connie is digging and licking the fireplace.

Lick granuloma

Also called acral lick dermatitis, this is a condition in which the dog repetitive licks a certain area of the body, often an area on the front legs. This may be due to an injury or pain or discomfort (not necessarily the area where the dog is licking). This licking will eventually cause the area to become inflamed and then infected, which causes the dog to lick more, to start a cycle of self-trauma, inflammation and infection.

Triggers for this include allergies, joint disease, other painful conditions, separation related problems, noise sensitivity, as well as any of the causes or ARBs mentioned above.

Vet treatment is always required in these sorts of cases.

What can I do if my dog has a repetitive behaviour and I need help?

The blog post “Border collie repetitive behaviour – 14 treatment tips” will give you some ideas about how to help your dog. However, it may be best to contact a behaviourist to ensure that you are giving your dog the best chance of recovery.

Please get in touch if needed, I’ll be very happy to help!

References:

Bécuwe-Bonnet, V., Bélanger, M.-C., Frank, D., Parent, J. and Hélie, P. (2012) Gastrointestinal disorders in dogs with excessive licking of surfaces. Journal of Veterinary Behavior, 7(4), 194-204.

Corridan, C.L.; Dawson, S.E.; Mullan, S. Potential Benefits of a ‘Trauma-Informed Care’ Approach to Improve the Assessment and Management of Dogs Presented with Anxiety Disorders. Animals 2024, 14, 459. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani14030459

d’Angelo D, Sacchettino L, Carpentieri R, Avallone L, Gatta C, Napolitano F. An Interdisciplinary Approach for Compulsive Behavior in Dogs: A Case Report. Front Vet Sci. 2022 Mar 24;9:801636. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2022.801636. PMID: 35400099; PMCID: PMC8988433.

Diagnosis and management of compulsive disorders in dogs and cats. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract. 2003 Mar;33(2):253-67, vi. doi: 10.1016/s0195-5616(02)00100-6. PMID: 12701511.

Galli, G., Uccheddu, S., & Menchetti, M. (2024). Fly-catching syndrome responsive to a gluten-free diet in a French Bulldog. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association, 262(3), 1-3. Retrieved Jul 6, 2024, from https://doi.org/10.2460/javma.23.09.0515

Hall, N.J., Protopopova, A. and Wynne, C.D.L. (2015) The role of environmental and owner-provided consequences in canine stereotypy and compulsive behavior. Journal of Veterinary Behavior, 10(1), 24-35.Harvey, N.D.; Craigon, P.J.; Shaw, S.C.; Blott, S.C.; England, G.C.W. Behavioural Differences in Dogs with Atopic Dermatitis Suggest Stress Could Be a Significant Problem Associated with Chronic Pruritus. Animals 2019, 9, 813. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani9100813

Langen, M., Kas, M. J., Staal , W. G., van Engeland , H., & Durston , S. (2011). The neurobiology of repetitive behavior : of mice…. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews,

35(3), 345 355.

Luescher AU. Diagnosis and management of compulsive disorders in dogs and cats. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract. 2003 Mar;33(2):253-67, vi. doi: 10.1016/s0195-5616(02)00100-6. PMID: 12701511.

Luescher, U.A., McKeown, D.B. and Halip, J. (1991) Stereotypic or Obsessive-Compulsive Disorders in Dogs and Cats. Veterinary Clinics of North America: Small Animal Practice, 21(2), 401-413.

Mills, D., & Luescher, A. (2006). Veterinary and pharmacological approaches to abnormal repetitive behaviour. In Stereotypic animal behaviour: fundamentals and applications to welfare (pp. 286-324). Wallingford UK: CABI.

Mason, G.J. and Latham, N. (2004) Can’t stop, won’t stop: is stereotypy a reliable animal welfare indicator?

Noh, H.J., Tang, R., Flannick, J. et al. Integrating evolutionary and regulatory information with a multispecies approach implicates genes and pathways in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Nat Commun 8, 774 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-017-00831-x

Overall KL, Dunham AE. Clinical features and outcome in dogs and cats with obsessive-compulsive disorder: 126 cases (1989-2000). J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2002 Nov 15;221(10):1445-52. doi: 10.2460/javma.2002.221.1445. PMID: 12458615.

Overall, 2013 [39] page number 276, chapter 7

Salonen, M., Sulkama, S., Mikkola, S. et al. Prevalence, comorbidity, and breed differences in canine anxiety in 13,700 Finnish pet dogs. Sci Rep 10, 2962 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-59837-z

Tatemoto P, Broom DM, Zanella AJ. Changes in Stereotypies: Effects over Time and over Generations. Animals (Basel). 2022 Sep 20;12(19):2504. doi: 10.3390/ani12192504. PMID: 36230246; PMCID: PMC9559266.

Tiira K, Hakosalo O, Kareinen L, Thomas A, Hielm-Björkman A, et al. (2012) Environmental Effects on Compulsive Tail Chasing in Dogs. PLOS ONE 7(7): e41684. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0041684

Whitehouse, C. M., Curry-Pochy, L. S., Shafer, R., Rudy, J., & Lewis, M. H. (2017). Reversal learning in C58 mice: Modelinghigher order repetitive behavior. Behavioural brain research, 332, 372-378.